The recently concluded winter storm recovery efforts provided the Jordanian regime with a welcome respite from the array of issues that currently occupy center stage in public debates. These include—but are not limited to—the Syrian refugee crisis, parliamentary corruption, and proposed “political reforms.” Nevertheless, there is another issue that eludes the notice of journalists and analysts, one significantly more sensitive than the topics capturing daily headlines. As the kingdom’s citizens and residents look tentatively towards the future, they wonder whether the state will continue to provide them their daily bread.

A Brief History of the “Bread Subsidy”

Jordan is one of the largest per capita spenders on food subsidies in the world. State intervention in the market accelerated dramatically beginning in the 1960s. Supply and price regulations first included products such as wheat, petroleum, and sugar. However, they subsequently incorporated coffee, tea, cigarettes, powdered milk, poultry, and rice. These policies were part of a larger trend that saw the expansion of state-sponsored social safety nets. The state imported many basic goods, subsequently setting maximum retail prices to alter market outcomes in favor of the consumer. Expanding state welfare was further spurred on by domestic inflation and increases in the cost of living in the early 1970s. The regime initially enacted this expansion in subsidies to appease public sector employees (i.e., members of the civilian bureaucracy and the military), who were subjected to low levels of growth in state salaries. However, the general application of subsidies benefited the majority of the population in Jordan. This commitment was institutionalized in the 1974 creation of the Ministry of Supply, which became responsible for administering subsidies for politically sensitive goods.

Similar to many of its neighbors, the successful state-led economic development model of the 1960s and 1970s gave way to the regional recession of the mid-1980s. A decline in oil prices led to a drastic fall in both foreign aid and labor remittances. Coupled with the limitations of state-led economic development as implemented in Jordan, the regime faced a fiscal crisis. In this context, the regime elected to turn to international financial institutions and the local private sector for budgetary relief and capital investment beginning in the 1980s. Various negotiations and debates resulted in a structural adjustment program that included the privatization of state-owned enterprises, cuts in state employment, and the removal of various subsidies. Reductions in government spending would continue through today, a trend first instigated in 1988 when the devaluation of the Jordanian dinar increased the cost of maintaining previously wide-ranging subsidies. Three years later (1991), rationing was introduced for previously supported products such as rice, sugar, and powdered milk. Ultimately, most subsidies were severely curtailed or abandoned. Today, all-purpose flour stands as one of the few remaining universally subsidized basic goods in Jordan.

As a result of continuous fluctuations in international commodity prices, the regime’s provisioning of discounted all-purpose white flour—known as the “bread subsidy”—now purportedly accounts for one of the largest expenses in Jordan’s annual budget. The IMF has deemed the flour subsidy a blatant and unsustainable inefficiency and has advocated reallocating public expenditure and “phasing out poorly targeted and costly subsidies.” The fund justifies such recommendations on the basis of its assessment that high levels of public debt limit the kingdom’s fiscal flexibility.

In the 1960s, bread prices were regulated through the sale of discounted wheat to flour millers who then sold all-purpose flour to local bakeries at a subsidized price. For the next twenty years, the wheat subsidy continued unabated, with bread prices increasing slightly from five qurush (0.35 qurush when adjusted for inflation) to seven-and-a-half qurush per kilogram in the late 1970s, where one Jordanian dinar (JD) is comprised of one hundred qurush. Wheat subsidies were provisionally lifted in 1996 to satisfy IMF loan requirements regarding levels of government spending. Consequently, the price of bread reached twenty-five qurush per kilogram before the state partially backtracked on its subsidy reforms following the bread riots in Karak (August 1996). The new subsidized price was sixteen qurush per kilogram of standard quality bread, made from local flour. It has remained the same to this day.

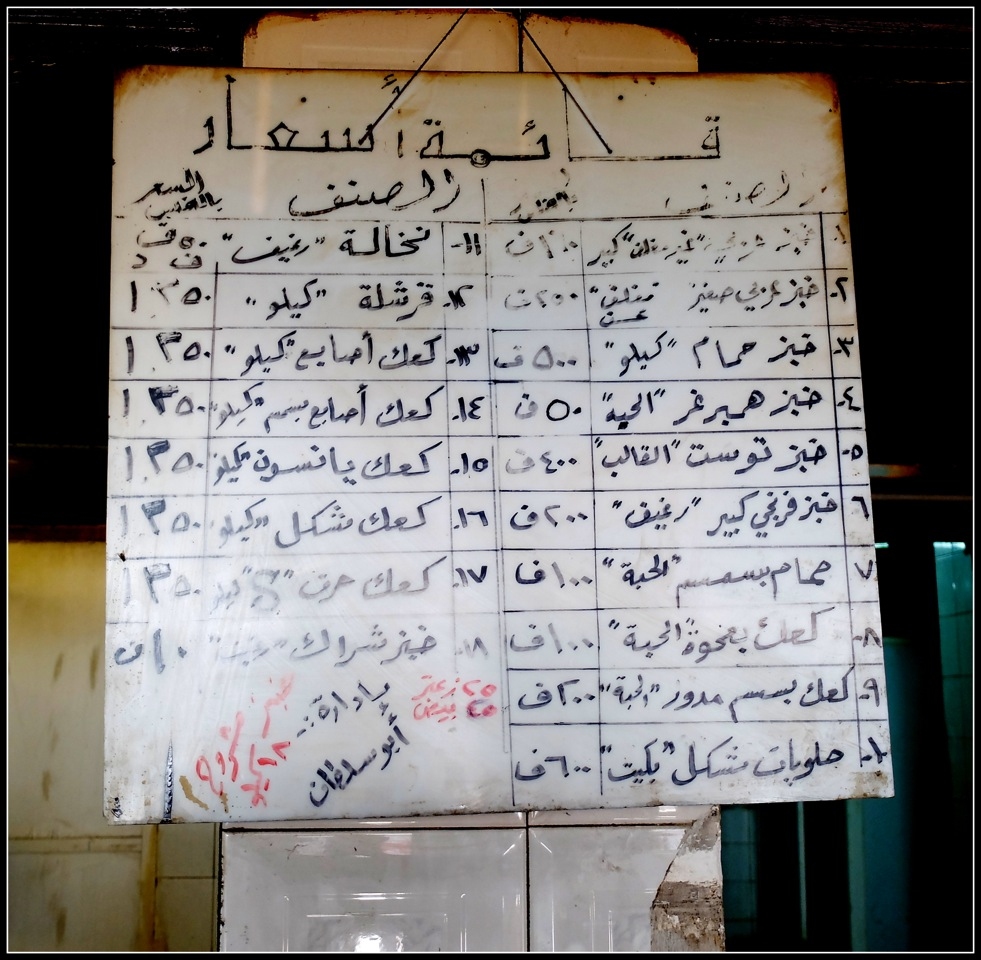

[Price list of breads at a local bakery in Sweileh. Image by José Ciro Martínez]

Over the last three years, successive Jordanian cabinets have severely curtailed support for wheat and fuel-based products at the behest of international organizations and donors. Following the dramatic rise in global wheat prices in the mid-2000s, the government stopped subsidizing wheat and wheat-based products in 2008. It currently only subsidizes all-purpose flour. In this system, the government purchases wheat on the international market and sends it to private millers who oversee its conversion into flour. The flour is then sold through government channels at regulated, below-market prices to bakeries around the country. The latter are sold subsidized flour according to quotas set by the Ministry of Industry and Trade, which is responsible for providing the flourmills with subsidized wheat. Only baked products, frequently bread, that are sourced directly from all-purpose flour (a combination of hard and soft wheat) are covered by the flour subsidy. Since this new system was enacted, bread has been indirectly subsidized by the Ministry of Industry and Trade, which sells discounted flour to local bakeries at a price of thirty-five dinars per ton while buying the equivalent amount on the international market for an average of 301.5 dinars. This policy costs Jordan around 265 million dinars (374.25 million dollars) a year to maintain a price of sixteen qurush (0.23 dollars) per kilogram of bread.

Residents of Jordan are estimated to consume eight million loafs of standard khubz ‘arabi (the local variant of pita bread) a day, averaging around ninety kilograms of bread per person annually. Bread’s place in the Jordanian diet is not only linked to its popularity, but also to the consistency of its price. Throughout the last forty years, the price of bread has remained far more stable than that of any other good such as sugar, rice, and milk powder. Whereas the latter were affected by a variety of approaches to state-led management (e.g., subsidies, rationing, and food coupons), governmental competence has been notable and persistent in ensuring the provision of cheap flour to the kingdom’s bakeries. As a result, subsidized bread has not only been a dietary staple. It has also been a mainstay of the regime’s social contract with its citizenry.

The Politics of Flour Subsidy Reform

All indicators in Amman point to a government intention to alter the flour subsidy. Yet few venture to guess how it will do so. Opposition figures have reported that the government has already tendered contracts for the production, distribution, and implementation of electronic “smart cards” to be used by Jordanian consumers in bakeries. Simultaneously, Ministry of Industry and Trade spokesmen seem to surface weekly to ensure the citizenry that there will be no rise in bread prices or to promise that direct cash subsidies will be used to avoid any hardships. Despite government guarantees, an array of bakers across the country have conveyed their incredulity, perplexed at how exactly the government intends to implement electronic technologies in all of Jordan’s bakeries or distribute cards linked to scant bank machines in rural areas. Consumer protection organizations have called for the formation of expert committees to study the subject in more detail. Notably, the administrative body of the Bakery Owners Association (BOA) has threatened to resign if authorities impose a smart card system rather than direct cash subsidies. Accordingly, these cash disbursements would seek to offset the difference between bread’s subsidized price of 0.16 dinars per kilogram and the expected free-market price of 0.38 dinars per kilogram.

Potential flour subsidy reforms are part of a larger story, one that began in the late 1980s following various Jordan-IMF agreements that sought to reform the country’s economy by reducing government deficits through austerity measures. The reforms have for the most part contributed to increasing levels of socio-economic inequality. Only a narrow stratum of the country’s elites have benefited from privatization and liberalization policies, which unraveled the state-centered economy and opened the country to foreign investment. Such policies barely addressed income inequality and wage-level rigidities. Official unemployment rates have remained stagnant at anywhere between ten to fifteen percent for the past two decades, with rates among those younger than thirty hovering around thirty-five percent. Coupled with higher utility prices, an increasing tax burden and the myriad effects of unemployment, incomes have been slowly redistributed in favor of the rich, resulting in lower per capita income and a shrinking middle class.

Most recently, Jordan’s Finance Minister Umayya Toukan has confirmed the imminent disbursement of 258 million dollars, the third installment of a larger thirty-six-month IMF 2.06 billion dollar “Stand By Agreement” loan. These funds are aimed at supporting the Palace-led program of reforms that seek to improve both macroeconomic stability and fiscal balance while fostering growth and allegedly protecting the most vulnerable segments of the kingdom’s population. Much like its predecessors, such reforms will focus heavily on macroeconomic indicators, failing to prioritize the social implications of imminent changes on the lower classes. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) reports are hardly alone in criticizing the “over-dependence on the use of quantitative methods of analysis,” when addressing the multidimensional characteristics of development. Such methods “can present a slightly distorted picture of human development,” especially for assessing the impact of structural adjustment reforms on the working and rural poor. In the past, the elimination of key subsidies has only aggravated the conditions of already vulnerable sectors in the country. The tenuous nature of employment and low levels of household savings mean that a sizeable amount of Jordanians live near the poverty line. Thus, sudden shocks in the price of basic goods can result in a disproportionate increase in the quantity of working and rural poor.

The government recently implemented the first in a set of problematic subsidy reforms. Universal fuel subsidies were slowly phased out over a two-year period before being completely removed in November 2012. To remedy public discontent, the state offered qualifying beneficiaries (with yearly incomes under eight hundred dinars) seventy dinars a year to allegedly counteract fuel price increases. Public sector employees, government and military retirees, social security pensioners and National Aid Fund beneficiaries receive cash compensation from branches of the local Housing Bank. Others must go to the offices of the Income and Sales Tax Department for their disbursements. Paradoxically, the Royal Council and parliament had initially increased fuel subsidies as part of their response to the uprisings throughout the region in mid 2011. Although the changes in November 2012 precipitated significant protests, state repression, broad-based apprehension shaped by the situation in neighboring Syria and other factors meant they did not escalate to levels significant enough to force the hand of the regime.

Under the current proposal to reform the flour subsidy, state authorities would merge reimbursements for fuel and bread through an electronic smart card mechanism that would permit recipients to withdraw cash from ATMs across the country. However, ministerial spokespersons have repeatedly emphasized that all options are still on the table, including variations of the smart card system or direct cash transfers. In relaying their skepticism, some middle and working-class consumers appear quite conscious of the blatantly unequal distributional implications that have resulted from previous efficiency-seeking programs promoted by international donors and organizations. Prime Minister Abdullah Ensour and his ministerial team have been cautious in their approach. They know well that market-based policy prescriptions that focus on macroeconomic stability at the expense of the less privileged may very well instigate the type of broad-based mobilization that the Hashemite dynasty has been incredibly skillful at preventing over the last forty years.

.jpg)

[Staff at a bakery in Sweileh preparing bread. Image by José Ciro Martínez]

The Ministry of Industry and Trade, which supervises the purchase of wheat and the distribution of subsidized flour, has taken the lead in arguing for the elimination of the “bread subsidy.” The Ministry’s spokesmen have consistently articulated the current government’s preference for the proposed smart card system. Together with Prime Minister Ensour, key state officials have made clear their intention to implement this brand new system, promoting their preference through age-old political strategies. Much like the previous fuel price reforms, government ministers have emphasized the disjunctures in a universal subsidy system that equally benefits the poor and the rich, nationals and non-nationals. In addition, dishonest bakery owners, corrupt government employees and injurious foreign agents have all been blamed for the misuse of subsidized flour. Some staffers in the Ministry of Industry and Trade are accused of being in cahoots with flour millers and bakery owners so to unduly profit during the process of converting wheat to flour. Crooked shop owners are charged with using discounted flour for, among other things, animal feed, costlier baked goods and illegal sales on the black market. Foreigners and refugees are blamed not only for increased consumption but also for smuggling subsidized flour into neighboring countries. Notably, the official discourse maintains that there is no intention to raise the actual price of bread for Jordanian citizens.

Neither Bread Nor Freedom

One day, as we slowly made our way past the town of Zarqa, about halfway up the rural highway that leads north towards the Syrian border and Za‘tari refugee camp, Ustadh (Teacher) Ahmad reflected out loud to me on the Jordanian penchant for bread. A lower middle-class resident of Amman and an instructor at one of the bourgeoning foreign language institutes now housed in Jordan’s capital, Ahmad draws a modest but adequate salary. It is enough to feed his family of seven and take an occasional family outing on the weekends. We conversed about the imminent economic reforms during one of his bi-weekly trips to Za‘tari, where he volunteers for a local Islamic charity.

Each day, countless Jordanian families of every social class buy large stacks of bread, what the Egyptian migrant bakery workers refer to as al-‘aysh (literally, life, figuratively, bread). Ustadh Ahmad notes that, “my family of seven alone eats around ten kilograms of bread a week.” He tells me, “Breakfast everyday is a bread-heavy affair, and my children take sandwiches of falafel or signora (packed lunch meat) everyday to school.” Bread is the traditional appendage to many Jordanian meals. In addition, its low price helps ensure access to rudimentary levels of subsistence among the poor and a quickly deteriorating quality of life amongst the dwindling middle class. In addition, bread’s place in the collective consciousness ensures that its distribution and provision are intimately linked to governmental legitimacy. Ahmad reminds me that, “without the subsidy, making ends meet would be a far more difficult equation.”

Ahmad’s critique of governmental decision-making is double faceted and piercing. He does not just resent the government’s disregard for his own situation as a middle-class Jordanian national but also its continued emphasis on ensuring that governmental assistance only apply to Jordanian citizens. As the son of displaced Palestinians, and a reluctant citizen of a country he “admires” for its ability and willingness to welcome hundreds of thousands of refugees, such intolerance is agonizing. He reasons that if anyone needs the subsidies, it is the refugees, the internally displaced and the bidun (stateless).

In an attempt to enhance regime legitimacy and popularity, key officials have been deploying a worryingly exclusionary nationalism. Just over a month ago, Prime Minister Ensour stressed that the bread subsidy will continue, but only for Jordanians, all in a bid to curb what he describes as “the wastage of bread” in the country. Under the cabinet’s initial plan, the subsidy would only apply to bread, rather than flour, and all Jordanian citizens with valid identity cards would be given a smart card with cash compensation for the difference between subsidized and market prices. This plan would not halt the allotment of government support to those social classes that need it least, as there is no income-level qualification similar to the fuel subsidy re-imbursement. It seeks instead to tug at the purse strings of the Kingdom’s citizens, off-put and resentful at the rising property and food prices to which the influx of refugees has undoubtedly contributed. Through such statements, the government hopes to legitimize a political project with unequal economic outcomes. By aggrandizing nationalist values, it hopes to replace the deeper meanings the citizenry assigns to the availability of subsidized bread with attachments to stability, peace and a tolerant (but exclusionary) vision of Jordanian identity. What attempts to counteract the steep price increases of products the government once subsidized may mean for the ballooning number of refugees in the country is an open question.

Like many of his fellow citizens, Ahmad knows well the immediate impact of alterations in government food subsidies. Implicit and explicit in many similar critiques voiced throughout the kingdom are not just a disquieting fear of a declining quality of life and the specter of hunger. Such threads contain a more expansive indictment that goes beyond targeting the economic measures themselves. The price and provision of bread should be discussed openly and constantly Ahmad tells me, “al-‘Aysh is a pillar of our everyday existence, its significance goes far beyond standard political calculations and cannot be decided by those ignorant of our daily struggles.” Ahmad continues, “We have no say in the system except when we protest. Our votes, our approval, our voice is worth nothing except when they seem dangerous.” Ahmad, various bakery owners and the many concerned Jordanian citizens I have interviewed view the government’s rhetoric of improving welfare and extending civil liberties as failing on their own terms. They foresee neither bread nor freedom, only hunger and autocracy.